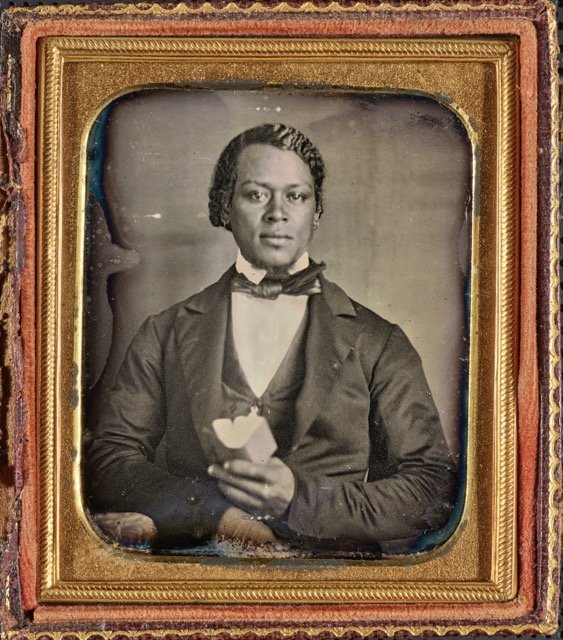

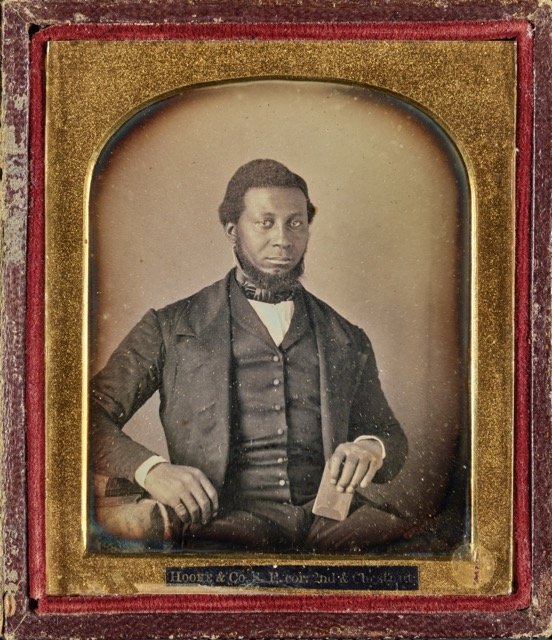

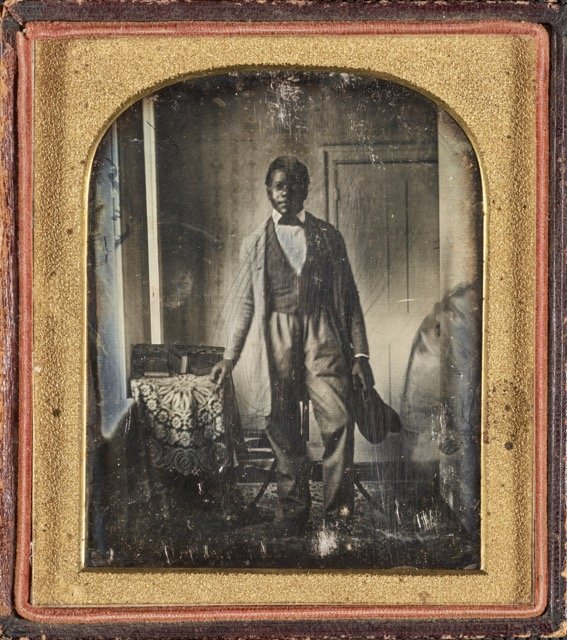

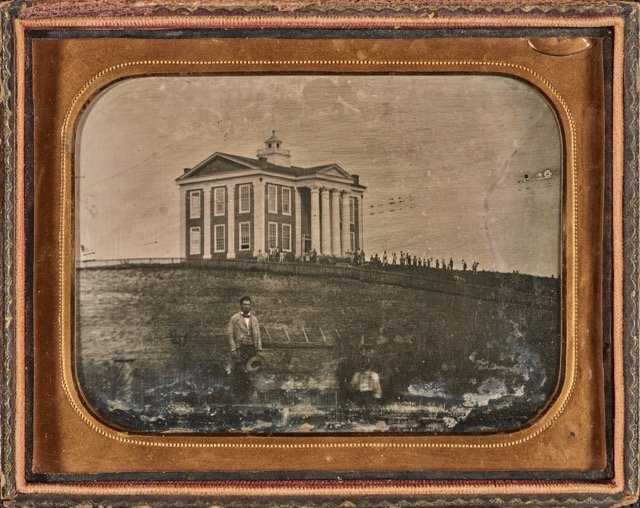

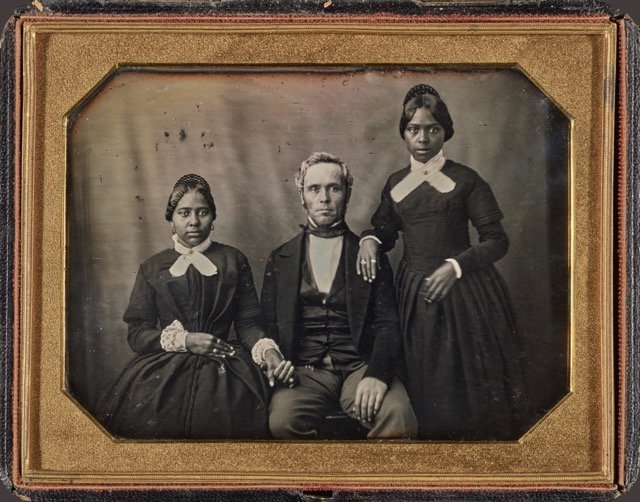

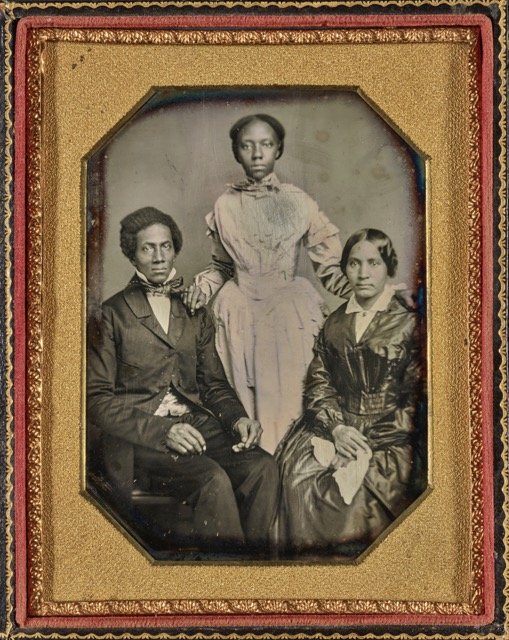

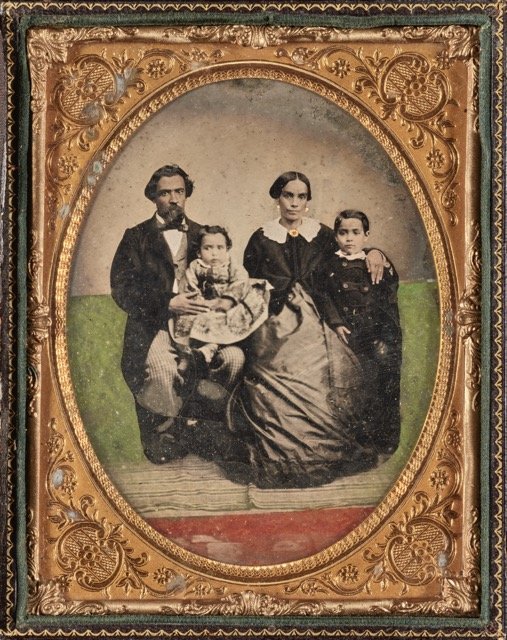

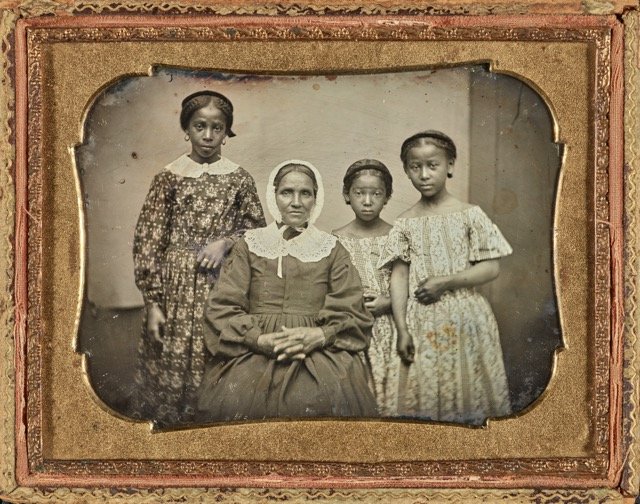

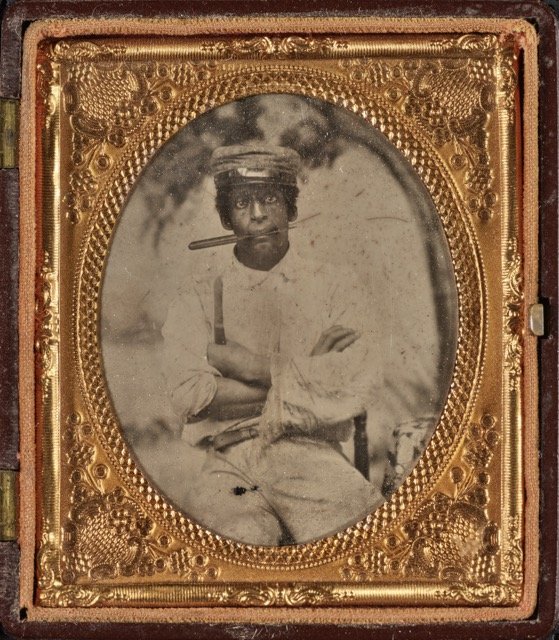

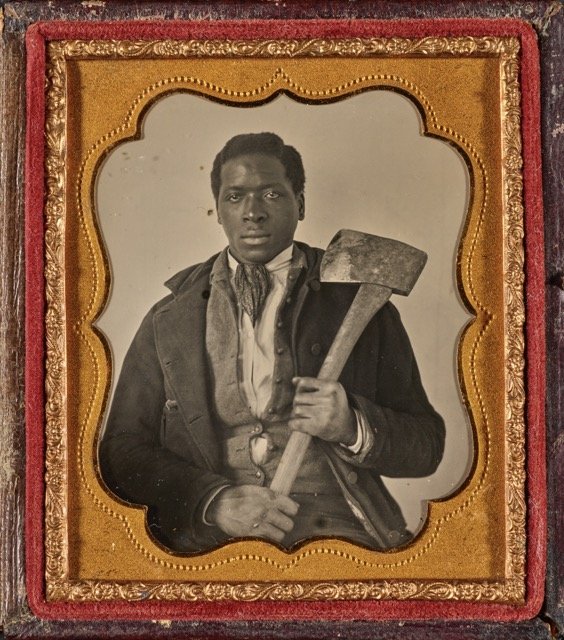

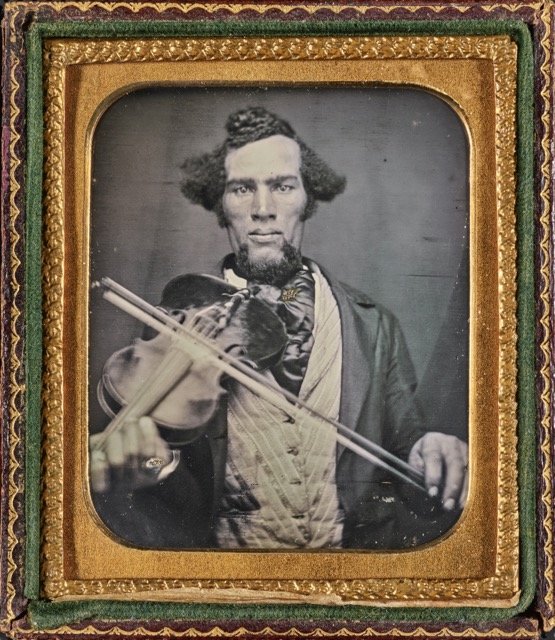

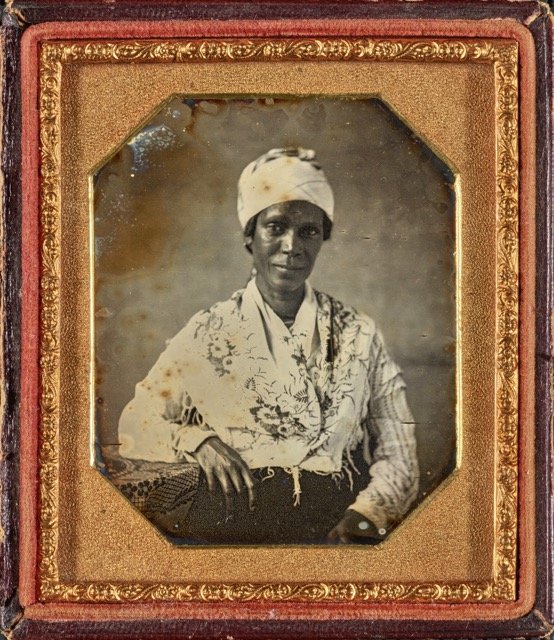

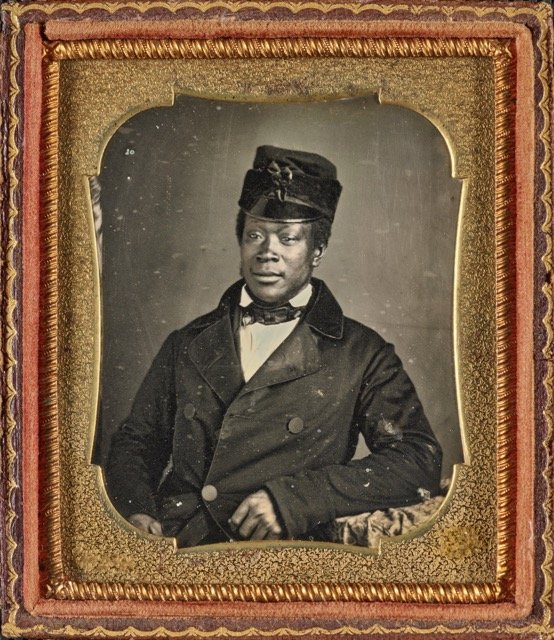

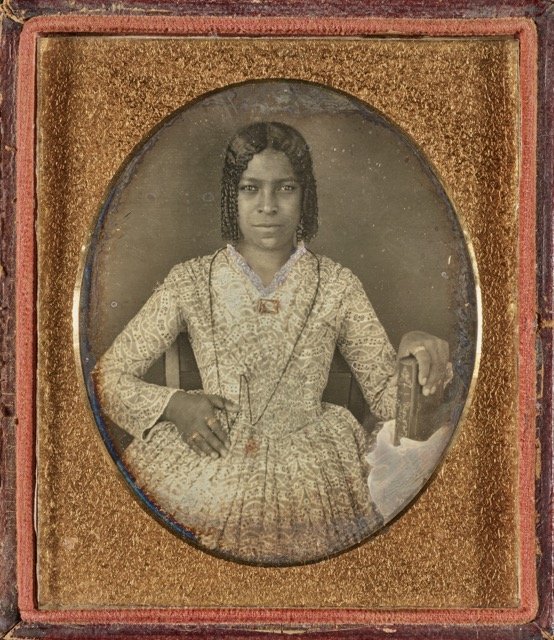

“I Am Seen…Therefore, I Am: Isaac Julien and Frederick Douglass“ brings together early unseen photographs of African Americans from the 1840s and 1850s from the collection of Greg French, and the works of pioneering African American photographers of the same period.

It juxtaposes them with Sir Isaac Julien’s Lessons of the Hour, a contemporary meditation on the life and legacy of Douglass and the power of images. Together, these striking images stage a dialogue between the local and the global, between Douglass’s encounters with Hartford and their relation to his larger national and international interventions in his unfinished quest for social justice for African Americans.

Explore the photographers…

The daguerreotype was an early photographic technique invented in France by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre and announced publicly in 1839.

The process involved coating a copper plate in silver, polishing it like a mirror, sensitizing it with chemicals, and exposing it to light inside a camera obscura pointed at whatever was to be photographed.

The plate was then treated with hot mercury to develop an image. Improvements to the process soon reduced the exposure time needed to capture an image from over a minute to twenty seconds by the mid-1840s and finally down to a few seconds to 1850. The resulting photographs were incredibly sharp but were monochromatic (unless hand tinted) and could not be duplicated.

Explore the process in the video below:

Daguerreotypes became exceptionally popular across America during the 1840s. The cost of a daguerreotype ranged from around 25 cents to $6 or more depending on size and quality. In today’s money that range is about $10 to $250. But they were cumbersome to make and the cost made them inaccessible to some people.

By the mid-1850s, daguerreotypes were superseded by quicker, simpler, and cheaper photographic techniques like ambrotypes, made on glass, and by tintypes, made of thin sheets of inexpensive iron. The advent of printed paper photographs in the 1860s truly made photographs available to almost every American.

“It is evident that the…universality of pictures must exert a powerful though silent, influence upon the ideas and sentiment of present and future generations.“

FREDERICK DOUGLASS, FROM “LECTURE ON PICTURES,“ 1861